By Dave McRae

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s hard-line rhetoric in recent weeks on the fatal shooting of drugs suspects has prompted many to question whether Indonesia is contemplating a Rodrigo Duterte-style war on drugs. Jokowi was spurred to comment by the seizure of a one tonne shipment of methamphetamine to Indonesia from Taiwan, reportedly the largest seizure in Indonesia’s history. Indonesian authorities shot dead a Chinese national during the interception.

“Now the police and the military are truly firm…. particularly against foreign drugs distributors entering Indonesia, if they resist a little bit, just shoot them immediately, as we are truly in an extreme emergency situation when it comes to narcotics,” Jokowi said on 21 July, about a week after the seizure.

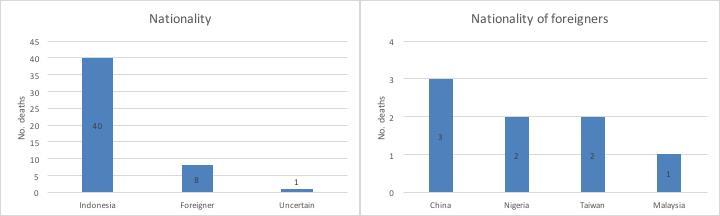

Jokowi’s comments reflect a clear upswing in fatal shootings of narcotics suspects this year, albeit not on a scale approaching the campaign of extrajudicial killings in the Philippines. In the first seven months of 2017, Indonesian authorities shot dead at least 49 narcotics suspects. Another suspect died in police custody in January, with police saying they suspected a heart attack. This is based on figures I have compiled from keyword searches of media reportage. Although imperfect, I am unaware of any comparable publicly available government data. Using similar methodology, I identified only 14 fatal shootings in 2016 and 10 fatal shootings in 2015.

Given the methodology used to compile these figures, it is likely that there have been additional shootings. For 2017, my figures match closely with a public announcement by Police Chief General Tito Karnavian on 8 May, however, that authorities had fatally shot 31 suspects. My figures show 32 deaths to that date.

Source: various Indonesian media reports

The majority of suspects fatally shot in 2017 have been Indonesian citizens, comprising 40 of 49 deaths. But foreigners are significantly over-represented among fatalities, at 8 of 49 deaths* or 16 per cent, given they comprise a tiny minority of drug arrests. Of 1,238 suspects arrested by the National Narcotics Agency (BNN) in 2016, for example, only 21 were foreign citizens, or 1.7 per cent. This over-representation is consistent with a broader trope of the Indonesian government’s “drugs emergency” rhetoric that foreign drugs criminals are destroying Indonesia’s future generations.

Inevitably, Jokowi’s comments in July raise the question of whether the sharp increase in the number of killings reflects deliberate government policy to deter narcotics crime. Certainly, hard-line rhetoric on shooting drugs suspects has been building in Indonesia for more than a year, although senior public officials have typically tread a fine line in their statements, being careful not to issue an unqualified order to kill.

Jokowi’s own statement in June 2016 on International Anti-Narcotics Day was typical, instructing police,“Pursue them, arrest them, beat them, strike them hard! If the law allows, shoot them!” Police Chief Karnavian has similarly toed this line, saying in January following the first five fatal shootings of the year, “Drug distributors, if you are still doing it, poisoning our nation’s children, and then you resist when you are arrested, then it will end the same way, here as well, in the morgue.”.

Even BNN Chief Budi Waseso, who has bent the line on extra-judicial killings further than most, stuck to this line when asked this week by the influential Tempo magazine about Jokowi’s statements. “The implementation is different in the Indonesia and the Philippines. In the Philippines, distributors are [just] shot directly. In Indonesia, it’s only the ones that resist officers.”

Even if such rhetoric does not amount to an explicit instruction to kill, it is not difficult to see how it could create a permissive environment for the fatal shooting of suspects.

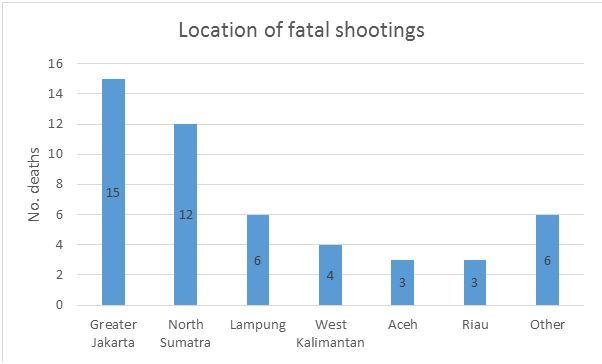

Fatal shootings are concentrated in several provinces: North Sumatra and Jakarta account for half of all shootings, with Lampung, Aceh and West Kalimantan also showing high incidence. This concentration could reflect the fact that several of these provinces are entry points for narcotics to Indonesia, or centres of activity for the narcotics trade.

The discretion of individual police commanders might also contribute. Police in North Sumatra, for example, have provided a running tally to the media of the number of drugs suspects shot dead in their province this year. Senior police in West Kalimantan, another province with a concentration of narcotics shootings in 2017, have also favoured tough language. Inspector General Musyafak, police chief in the province before April, told the media in October 2016 that he apologised in advance if his personnel shot dead drug distributors. Police had weapons to shoot criminals, not to show off, he said, although he added they must use them to subdue suspects, not murder them.

All incidents I have recorded resulted in only a single fatality or two suspects being shot dead. In more than one third of cases, the fatal shootings occurred well after the suspects had been arrested, when authorities took them to a secondary location to identify further suspects, or to point out where drugs and weapons were stored.

Whether at the initial point of arrest of a secondary site similar stories recur: most often the suspect is said to resist arrest or flee, often ignoring warning shots, after which police fatally shoot them. In a minority of cases, the suspects are said to have fired on police, brandished a weapon, attempted to seize a police firearm, or even to have rammed police with a vehicle.

But as Jim Della-Giacoma has previously observed in the case of police shootings more broadly in Indonesia, many of the accounts of the shooting sit uncomfortably with the police’s own regulation governing the use of fatal force. He writes:

[Indonesian Police Chief regulation No 8 of 2009] says that ‘the use of firearms shall be allowed only if strictly necessary to preserve human life’ and ‘firearms may only be used by officers: a) when facing extraordinary circumstances; b) for self defence against threat of death and/or serious injury; c) for the defence of others against threat of death and/or serious injury.’ This is Indonesian law, taken from the UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials, and this is what should be used to assess police actions, wherever in the country they occur.

Moreover, much as similar scenarios recur across media reports, the feature of these cases that really stands out is the lack of independent reportage by the media beyond statements provided by the police or BNN. It is rare for reports to contain any indication that the media have investigated further. In fact, media reports often run under headlines that implicitly approve of the killing or at least play up their drama, such as “Bang, a drug dealer shot dead”. Beyond periodic reportage of critical statements by legal aid or human rights organisations, little scrutiny is applied to the rationale for these shooting deaths.

And yet, as the numbers of narcotics suspects being shot dead in Indonesia grows, there is a clear need for critical reportage to scrutinise the circumstances under which these deaths are occurring.

This article first appeared at Indonesia at Melbourne.