By Duncan Graham

The Brits would have

loved it. Deep in the heart of East Java the Union Jack was carried with

pride, waved with vigor and cheered by thousands.

But the only

blondes bobbing in the swirling ocean of soccer fanatics were two benign

Belgians, disguising any assumption that they might be Dutch or

American. Their trick was to pull on Harry Potter cloaks of

invisibility, in this case T-shirts screaming love for Arema soccer

club.

Paul Beetens and Annie Aertsen need not have bothered. Had

the boisterous crowd known the couple was from the tiny royalty that has

become the darling of European soccer, they would have been mobbed as

heroes at Arema’s ginormous birthday bash in Malang.

The day-long

show celebrated 29 years of less than spectacular successes on the

field — Arema was last trounced by Persipura Jayapura — but almost three

decades of heartfelt hope and soul-wrenching prayer. With wet cheeks it

recalls 2010, the year of majesty when it reigned over the Indonesian

Super League.

To revive the fatigued ambition the fans painted

the town blue. Although Aug. 11 is the official 1987 birthday, the

police persuaded organizers to shift to the nearest Sunday to minimize

disruption. The tactic was a success. Total chaos was reduced by 5

percent — gridlock by marginally less.

The Belgian tourists

thought the event a hoot. And a roar, amplified by 100,000 Hondas, plus a

backing choir of Suzukis and Yamahas.

“It’s a celebration of

solidarity,” they shouted. “Everyone seems happy. We’re lucky to be here

at this time. We came for a trip to Bromo — and this is a bonus.”

Malang’s

followers did not get labeled Aremaniacs by holding soirees with the

gentry so security was intimidatory. “Was” because threat fatigue soon

set in — as it does wherever trouble is imagined. Suspicion is a

high-maintenance emotion with a short shelf life.

A squad from

the police’s Mobile Brigade (Brimob) in age-of-terror black vaulted from

a Barracuda Armed Personnel Carrier (APC) that looked like a giant

toad. They checked packs of tear-gas cartridges, slung Pindad SS1

assault rifles across their chests and swaggered into the front line.

The

everyday cops, eclipsed by this awesome show of military might, showed

their authority by pulling out traffic offenders and disarming riders

carrying flagpoles.

“To stop them being used as weapons,” said a

policewoman, who then used a confiscated stick to whack the bottom of a

fan giving cheek.

Arema’s birthday party is one great

do-it-yourself shebang, at odds with the official choreographed Aug. 17

Proclamation Day events where goose-stepping discipline rules. The

handmade banners often use English to add status, though the grammar and

spelling tended to dampen that desire.

Though the mob was

largely male the event was egalitarian. Women may have been outnumbered,

but they compensated with enthusiasm by pillion dancing and urging the

drummers to bang harder.

Teenage Fitri’s message across her

bosom was encouraging: “Football For Unity, Indonesia is not Iran or

Saudi Arabia, so a woman’s place is almost everywhere”.

The Union

flags were there to inspire. The UK teams are models for Arema fans who

wish their lads could be as skilled and focused as Manchester United.

In Malang it is the English leagues that excite. The fans trickled

through the gauntlet of gendarmes, and then opened throttles for

circuits around the flower beds before the town hall. The courtyard was

fronted by two blue fiberglass lions, so kitsch they would not make it

into a Disney cartoon movie.

Suddenly the police radios

sputtered and the uniforms dashed away. Clearly a fight had erupted, or —

shock, horror or maybe a suspicious package. Fortunately it was the

lunch bell and the packages contained the local alleged delicacy nasi

rawon (black beef soup).

This delighted the giggles seeking

selfies with men in black. The bullet-proof Barracuda began to melt. So

the doors were opened, letting the local guys goggle the weapons

wonderland. The greatest danger was not from a deranged knifeman but an

invisible toxin. The fans should have prayed for real winds of change.

Concentrated carbon monoxide kills. In lesser doses it sickens.

The

saddle dancers lost their balance, the banner boys began to flag, the

kids in lion masks stopped growling and started coughing. Arema’s

birthday is a fun show that should be on the tourist calendar, a

marvelous expression of organic togetherness.

But on a windless day in Malang it is a health hazard.

Duncan Graham is a journalist who resides in Malang, East Java, Indonesia.

Arema for life: Fans of Malang’s Arema soccer club, also known as

Aremania, stage a convoy during the club’s anniversary celebrations in

its hometown in East Java.(JP/Erlinawati Graham)(JP/Erlinawati Graham)

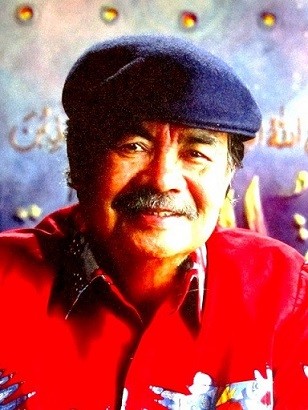

Amri Yahya Source: http://miesehati.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/amri-yahya.jpg

Amri Yahya Source: http://miesehati.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/amri-yahya.jpg Dutch troops with captured Indonesian fighters Source: http://www.verzetsmuseum.org

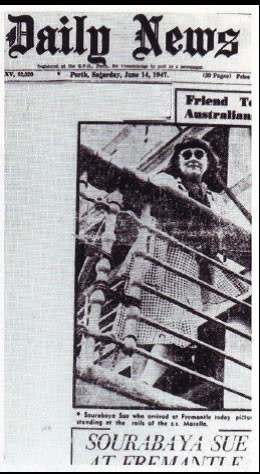

Dutch troops with captured Indonesian fighters Source: http://www.verzetsmuseum.org ‘Sourabaya Sue at Freemantle’, Daily News, 14 June 1947

‘Sourabaya Sue at Freemantle’, Daily News, 14 June 1947  Sydney Morning Herald, 25 July 1947

Sydney Morning Herald, 25 July 1947 Front page, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 1947

Front page, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 July 1947 The

Indonesian delegation arriving before the Lake Success UN Security

Council meeting: (left to right): Agus Salim, Foreign Minister; Dr.

Soemitro, Minister of Finance; former Premier Sutan Sjahrir,

Ambassador-at-large; and C. Thamboe, Minister of Foreign Affairs. Source: UN Photo archive.

The

Indonesian delegation arriving before the Lake Success UN Security

Council meeting: (left to right): Agus Salim, Foreign Minister; Dr.

Soemitro, Minister of Finance; former Premier Sutan Sjahrir,

Ambassador-at-large; and C. Thamboe, Minister of Foreign Affairs. Source: UN Photo archive. Photo

taken on 17 January 1948 on the deck of USS Renville shows (right to

left): Prime Minister Amir Syarifuddin, Setiadjit, Johannes Leimena, H.

Agus Salim, Ali Sastroamidjojo, and Latuharhary. Source: leimena.org

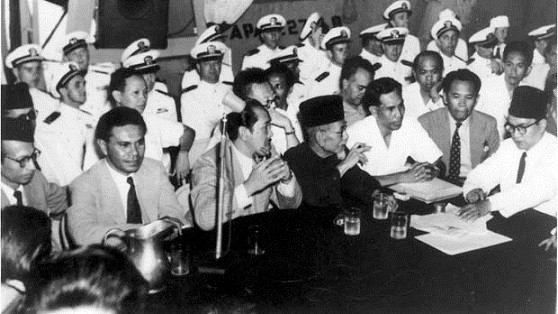

Photo

taken on 17 January 1948 on the deck of USS Renville shows (right to

left): Prime Minister Amir Syarifuddin, Setiadjit, Johannes Leimena, H.

Agus Salim, Ali Sastroamidjojo, and Latuharhary. Source: leimena.org The Round Table Conference in session Source: wikipedia

The Round Table Conference in session Source: wikipedia Jogjakarta, 16 November 1947, Good Offices Committee (GOC) Chairman Judge Kirby brings Dutch proposal Source: http://www.sukarnoyears.com/440australia.htm

Jogjakarta, 16 November 1947, Good Offices Committee (GOC) Chairman Judge Kirby brings Dutch proposal Source: http://www.sukarnoyears.com/440australia.htm